// By Brad Walker, Rivers Director December 17, 2014

Two-thousand-fourteen has been a very good year for the most subsidized mode of freight transport in the U.S. – river barges. Phase 1 of their bailout was initiated in the 2014 Water Resources Reform and Development Act (WRRDA) with a fleecing of the taxpayers for most of the barge industry’s remaining obligation to fund the money pit called the Olmsted Locks and Dam on the Ohio River – $525 million. Maybe you felt the hand pulling the money from your wallet on June 10, 2014.

The path to astronomical welfare levels for the barges has been long and costly.

The Past – A Brief History of River Welfare

Prior to the railroads, shipping by water made a lot of sense and despite being dangerous at times it required no expensive infrastructure. The rivers were cleared of debris and steamboat captains learned to navigate the river. After the railroads were built, river steamboat navigation essentially disappeared because it could not compete, though admittedly the 19th century railroads’ predatory and corrupt activities assisted in their dominance of freight transport.

Congress, for several reasons, including the need for jobs during the Great Depression, considered building a complex 9-foot barge channel on the Upper Mississippi River (UMR) and Illinois River using locks and dams. Ignoring both economic and ecology experts (see pages 21 and 22), as well as knowledgeable people within the U.S. Corps of Engineers (Corps), Congress proceeded with the construction in the 1930’s. It was also hoped that this modern inland waterways system (IWS) would compete with the railroads and lower their rates, though this could only have an effect on the shipping to and from the Gulf of Mexico.

The IWS has cost tens of billions of dollars to construct, operate, and maintain; virtually all of those costs have come out of the pocket of the taxpayers. Prior to 1986 the taxpayers paid every cent of infrastructure and operation of the IWS, a 100% subsidy. No other freight transport mode comes close to that level of corporate welfare. Barges were not required to contribute any funds to the system.

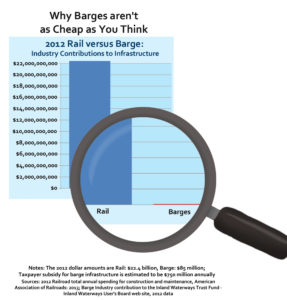

For those of you just itching to counter this with the argument that railroads got free land in the 1800s, please look here and here to see how the railroad expansion into and across the great plains benefited the country’s development. And for the highways subsidy, please see Figure 1. There really is no comparison with the barge industry subsidy except, as an April 15, 2013 Forbes article points out, space travel.

However, Congress finally came to the conclusion during the late 1970’s that a 100% subsidy for the IWS was excessive and managed to get a tiny contribution from the barge industry through a diesel fuel tax.

In 1986 Congress included a requirement in the Water Resources Development Act that obligated the barge industry to contribute money for the construction of new barge infrastructure and the rehabilitation of existing facilities. Revenue was collected in the Inland Waterways Trust Fund (IWTF) from the diesel fuel tax, initially set in 1978 at 4 cents and incrementally increased to 20 cents by 1995, on each gallon of fuel used by towboats on the IWS. It currently generates about $85 million each year and the fuel tax has not been increased since 1995. This fuel tax lowers the subsidy to about 92%; still by far the largest of any planet-based mode of transportation. At least the barge industry had some skin (or maybe just dandruff) in the game with what is essentially a form of a public-private partnership.

The Present

Each year Congress appropriates about $800 million for the construction, rehabilitation, operation and maintenance of the IWS for the Corps to spend, with the most costly portion being for maintenance. This amount is not adequate to effectively maintain the entire system, which currently has more than a billion dollars in maintenance backlog, but this is apparently all that Congress can stomach to appropriate for it. The inevitable result has been escalated degradation, requiring then costlier rehabilitation. Despite the obvious cost disparity between what is required and what is appropriated, Congress is unwilling to close the gap by requiring the barge industry to contribute anything for the cost of the operation and maintenance of the system that they completely depend upon.

Contrast that with the rail industry that typically spends $15 to $18 billion each year to operate, maintain and expand their system, while still making a profit (Note: Figure 2 includes rail equipment).

The IWS has also had a huge negative impact upon our large rivers over the last 80+ years. We have previously discussed the environmental condition of our rivers in previous articles here and here. To restore the rivers to a minimal level of health will cost us billions, and not a cent is expected to come from the barge industry that is primarily responsible for the damage. Because the projects were constructed before 1986 there is no requirement for those responsible to share in this environmental mitigation, yet they and their customers have benefited greatly from the IWS.

The barge industry unsurprisingly refuses to contribute to operation, maintenance, and environmental restoration costs or to significantly increase their contribution to the IWTF, but does want to expand the IWS infrastructure in segments where expansion is not justified, dependent of course upon the taxpayers paying at least half of the cost.

Meanwhile, annual barge traffic today on both the UMR and Illinois River has decreased since the peak in 1990 in total by about 30 million tons and is currently about half of what was projected in the 1970s to justify the Melvin Price Locks & Dam (See Figure 3 below).

The Future

Proposed New Locks on the Upper Mississippi River

Over the last two decades the barge industry has been pushing for the construction of new longer locks on the UMR and Illinois River, which will have a multi-billion dollar price tag. Their lobbying efforts culminated in the Corps’ Navigation and Ecosystem Sustainability Program (NESP) in 2004, which was finally authorized by Congress in the 2007 WRDA. The program includes much needed restoration projects supported by the environmental community, along with seven new locks and other much cheaper navigation improvement projects. After the program was authorized by Congress, the Corps provided its economic report on the locks showing that they are not justified and would likely result in a financial loss to the public. For details on NESP, review the report Big Price – Little Benefit, where you can read about the environmental / taxpayer community response to NESP.

Despite the locks being a loss for taxpayers and the environment, the new locks would be a great deal for special interests and the barge industry because only half of the project’s cost would come from the IWTF, with the remaining cost from the U.S. taxpayers.

No Assistant Secretary of the Army (ASA) has ever signed off on NESP, nor has any Administration ever included NESP in their budget. And since 2010, NESP has been unfunded by Congress. We believe that the lack of support for NESP by both the ASA’s and Administrations is consistent with our reason for opposing the locks – the Corps’ own economic report shows the locks are a bad investment, so no rational person would invest in them. NESP is moving along a potential timeline of Congressional deauthorization due to its lack of funding. The barge industry and the special interests that benefit from the IWS are working hard to find a solution to the lack of political support and funding for NESP.

Public – Private Partnership Scheme: Barge Industry Bailout – Phase 2

The solution the industry and their supporters are promoting is to get others to invest in the IWS so that the locks can get built as soon as possible and hopefully also reduce their 50% share of the costs ahead of time. The vehicle for this new idea was conveniently authorized in the 2014 WRRDA, which allows pilot projects to be proposed by non-federal government sponsors. The sponsors would be able to apply for federal loans to cover their portion of the project costs and would not require repayment to begin until 5 years after a project is substantially completed.

A mechanism to accomplish this is called a Public – Private Partnership (P3), which is a group of differing fiscal arrangements often used to privatize public infrastructure. The inadequately funded IWTF mentioned above is a form of a P3. For information regarding the “myths” of privatizing public works, review this information.

The fact that profit-motivated Wall Street investors have shown no interest in investing in NESP is further proof that it is a bad investment. If all they care about is making a profit, then they would not invest in something with such a terrible benefit-cost ratio. Unfortunately, the barge industry probably knows that the private sector will not invest in this P3 and is using this as an opportunity to get funding from states by raising taxes. If so, this is just another ploy to put the funding burden back on the taxpayers. Even worse, if state funding took the place of private investment (even in part), it could lower the 50% industry contribution.

So the alternative P3 being offered by the fiscally-challenged State of Illinois is to create the Inland River and Waterways Authority. The details of this Authority have not been revealed as yet, but we fear/expect that the new revenue stream will come from state taxpayer funds, not private investors, and will be used to reduce the IWTF obligation.

We are also concerned that the P3 process could be used to circumvent the Corps’ detailed construction implementation requirements for NESP that were included in the authorization in the 2007 WRDA. The requirements included incorporating cheaper small-scale and non-structural measures into the UMR and Illinois River IWS prior to building locks and then updating the economic analysis 5 to 7 years after these measures have been incorporated before Congress decides to approve the building of new locks.

The P3 approach is potentially the perfect scenario for a highly subsidized industry that provides marginal public benefits and is negatively impacting the river environment. It could cut their cost obligation percentage, reduce or eliminate oversight requirements, and would likely get the locks built without following the intended Corps plan. It is clear that the barge industry and their special interest supporters will be pushing to circumvent the requirements that protect the public and our environment. It is crucial that we continue to monitor this potential pilot project closely and if we see these red flags, to draw attention to them and try to prevent a bad deal before it is formalized. We want to make sure that if public funds are being used, that they are being used to benefit the public economically and environmentally.

Parting Thought

At the pace of the current and projected subsidy rate for the barge industry, the IWS may soon return to nearly a 100% subsidy level, which is really where the industry has always wanted to be. Ironically, with the introduction of privatized space travel, the barges may actually dethrone space travel and gain sole possession of the top notch for transport subsidies.

Does not all of this beg the question – Are some major segments of the IWS even worth keeping?