By Maxine Gill, MCE Policy Coordinator On Tuesday, Vice President J.D. Vance stepped in to tie-break a 50-50 vote split on the Senate’s version of the President Trump and Republican legislator-driven budget reconciliation bill. Today, the bill faces a vote in the House. The budget bill has gained national attention for the estimated $3.3 trillion…

Read MoreRadiation Exposure Compensation Act

By Christen Commuso, Policy Specialist As many of you know, the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act (RECA) expansion bill that we have worked on for several years was included in the GOP’s big budget bill, which has already passed in the Senate. I would like to acknowledge Senator Hawley for keeping his promise to our national RECA Working…

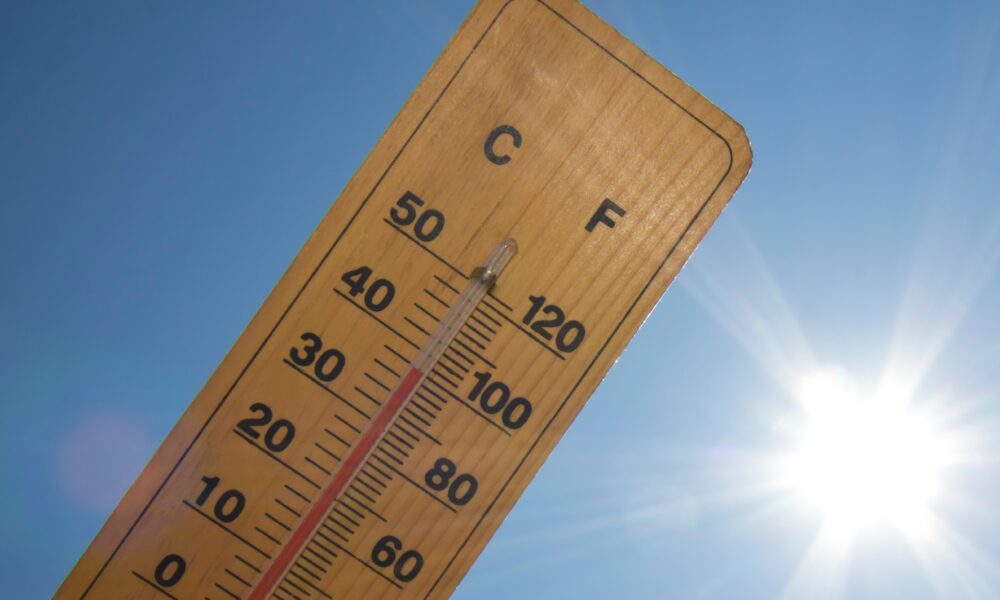

Read MoreExtreme Urban Heat Policy Action

It’s confirmed: Summer of 2024 was the hottest summer in recorded history, second only to 2023. While we enjoy the coming of spring, we must also prepare for the increasingly dangerous temperatures in store. MCE is doing so by creating a policy plan that will aim to help protect city of St. Louis residents from…

Read MoreA Letter from our Member, Dana Ripper

by Dana Ripper and Maxine Gill, MCE Policy Coordinator On Thursday May 29, the Missouri Department of Natural Resources hosted a public hearing discussing seven proposed poultry CAFOs in Lawrence and Newton counties. Missourians from across the state who strongly opposed these CAFOs gathered at the Pierce City High School Gymnasium to make their voices…

Read More2025 Legislative Session: Wins and Losses, Work Moving Forward

Written by our 2025 Legislative Intern, Kade Carnes. Thank you, Kade, for your incredible work this session! As of May 16th 2025, Missouri concluded its spring legislative session. As the dust from this most recent session settles, MCE wanted to highlight the hardfought wins and losses. MCE submitted ~65 pieces of testimony either online or…

Read MoreAI and Data Centers in Kansas City

By Makenna Nickens This article was originally published in our Spring Alert Newsletter that was delivered to MCE members in April 2025. Donate and Join now to start receiving your newsletter, other benefits, and to support our mission! For almost 20 years, the iconic Kansas City Star Press Pavilion has been a facet of the…

Read More