Download this in PDF form, here.

Unregulated Concerns

Missouri CAFOs are permitted and regulated under the Clean Water Act (CWA) and must meet regulatory requirements based on the conditions of this permit. Depending on the size of the facility – which is determined by the number and type of animals – CAFOs must maintain certain buffer and setback distances, provide neighbor notices, prepare Nutrient Management Plans (NMPs) and complete internal reports. If CAFO construction will disturb more than one acre of land, the operator must also obtain a land disturbance permit. See the DNR’s fact sheet on CAFO regulations here.

However, CAFOs generate many human health and environmental concerns that are not accounted for in their permit conditions. Therefore, many of these additional concerns – air emissions, workers’ safety, hormone and antibiotic use, and animal welfare – are virtually unregulated. These concerns are summarized below and you can learn more about them in MCE’s multimedia Story Map. See Additional Reporting Resources for ways that some of these unregulated concerns can be addressed.

-

Air Emissions

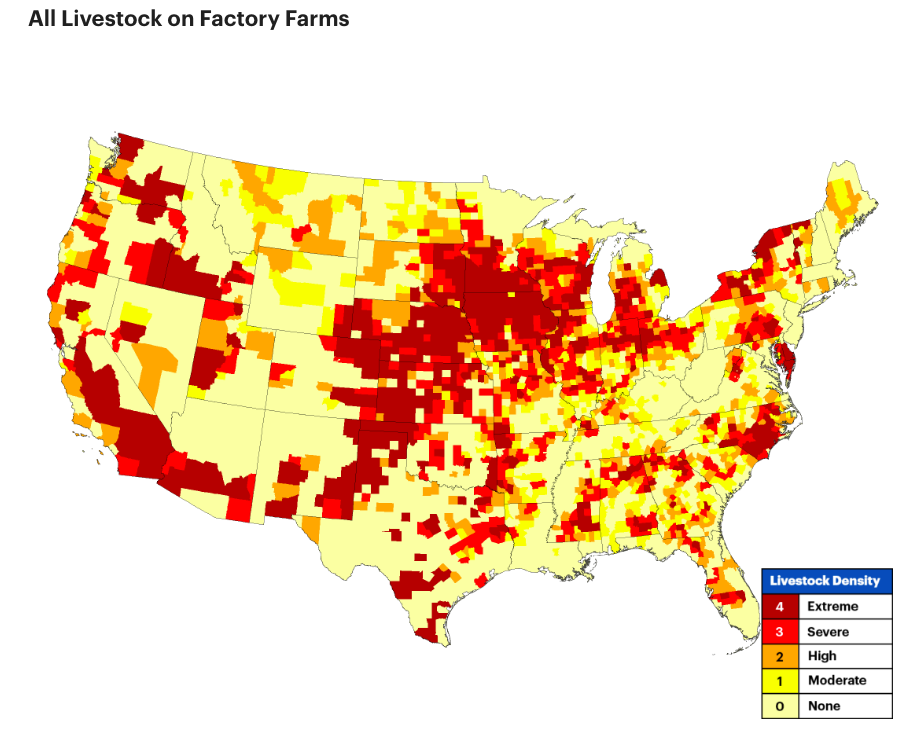

Agricultural industries produce about 80% of nitrous oxide emissions and about 35% of methane emissions in the United States. The largest source of agricultural greenhouse gas emissions is the livestock industry: more specifically, the waste produced by livestock animals (US EPA). CAFOs also produce ammonia, hydrogen sulfide, methane, and particulate matter (PM) – all of which have well-documented environmental and human health consequences (CDC). See the summary table below:

| Air emission | Environmental consequences | Human health consequences |

| Ammonia | Pungent odor | Respiratory irritation; severe cough; chronic lung disease |

| Hydrogen sulfide | Pungent odor | Eye and respiratory inflammation; olfactory neuron loss; death |

| Methane | Potent greenhouse gas | None |

| Particulate matter (PM) | Reduced visibility; acid rain | Chronic respiratory symptoms like bronchitis and asthma; impaired lung function |

The Clean Air Act (CAA) regulates air emissions to protect human health and the environment. CAFOs should qualify for CAA regulation as a stationary source of greenhouse gases and other emissions; however, the CAA has been made virtually unenforceable. In 2005, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) sought to gather more data on AFO emissions and offered participants in its voluntary emissions monitoring program temporary immunity from penalties for CAA violations through its Air Compliance Agreement. Thousands of AFOs and CAFOs signed on to the Agreement, which has effectively undermined any CAFO oversight under CAA, the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA), and the Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act (EPCRA) since 2005 (see this EPA report).

Before Missouri Senate Bill 391 passed in 2019, local governments could establish county health ordinances to regulate CAFO air emissions. However, SB 391 determined that county health ordinances may not impose standards on agricultural operations which are more stringent than state standards. Read more about SB 391 and local ordinances below under ‘Regulatory Changes’.

-

Worker Safety

CAFO work involves a number of human health risks. CAFO workers experience high rates of respiratory illnesses like bronchitis and asthma because of occupational exposure to air pollution, as well as frequent headaches, body aches, and nausea (CDC). Since CAFO employees operate heavy machinery and interact with animals, workplace injuries are common and sometimes fatal (NIH). Furthermore, livestock operations are breeding grounds for insects, pathogens, and viruses: workers with frequent exposure to animals and their waste may be the first to get infected.

Occupational safety concerns are a racialized issue. “A large percentage of factory farm workers are people of color including migrant workers from Mexico and other parts of Latin America” (Food Empowerment Project). This is no coincidence: employers actively recruit undocumented workers on temporary labor contracts because “they are less likely to complain about low wages and hazardous working conditions” (Food Empowerment Project). CAFO operators reportedly house migrant workers in company-owned trailers which may lack plumbing and other utilities and transport workers to facilities on overcrowded buses. Furthermore, language and cultural barriers may prevent migrant workers from understanding occupational safety risks and procedures, reporting concerns, and accessing healthcare and/or legal resources.

CAFO labor is not only dangerous, but racially-exploitative. Read more about environmental injustices caused by CAFOs here and about occupational safety concerns for food system workers from the Food Chain Workers Alliance.

-

Animal Welfare

CAFOs house anywhere from hundreds to tens of thousands of animals in crowded, poorly-ventilated buildings without space to move or access to sunlight, fresh air, and pasture. This environment produces extremely unsanitary living conditions, unwarranted stress, and suffering for animals. See the Socially Responsible Agriculture Project (SRAP)’s web page for more information about animal welfare concerns and a list of farm welfare groups which advocate for a more humane food system.

-

Antibiotic and Hormone Use

CAFOs crowd a massive amount of animals, feed, and waste in close proximity, which creates a breeding ground for bacteria. It has become common practice for factory farm operators to administer low-dose antibiotics to all animals– sick or healthy– to prevent disease outbreaks. However, bacteria develop resistance to antibiotics over time, therefore administering antibiotics to healthy animals is ultimately harmful and may hinder our ability to treat bacterial illness in human populations, as well. Read more about how CAFOs have impacted antibiotic resistance from the Western Organization of Resource Councils

Beef cattle and dairy cows are sometimes given supplemental hormones to stimulate growth and weight gain (federal law prohibits the use of hormones for hogs and poultry). Humans may be exposed to these hormones by consuming beef and dairy products The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) should regulate and label hormone use to ensure safe meat consumption, however labels can be misleading and some people believe that synthetic hormones are unsafe to consume at any level. However, these hormones may have unregulated and harmful impacts on aquatic life when animal waste contaminates surface and groundwater. Read more about the fate and effects of hormones from CAFOs in the ‘Background’ section of this EPA grant project.

-

Corporate Consolidation

“Eighty-five percent of the meat Americans consume is produced by four corporate giants – Tyson, Smithfield, Cargill, and JBS” (Public Justice). All of these corporations are known for using industrial methods to mass-produce inexpensive meat with little consideration for human, animal, or environmental welfare. Tyson, Smithfield, and Cargill all have operations in Missouri.

Over time, a smaller number of facilities (mostly owned by these corporations) have become responsible for producing a larger share of America’s meat. Corporate consolidation has simultaneously mapped the decline of the small farmer. Since larger farms

realize higher profits and depress prices for farm commodities, they quickly outcompete smaller farms with higher costs (USDA). Read more about CAFO expansion and corporate consolidation in the Food & Water Watch’s recent issue brief ‘Factory Farm Nation’.

CAFO operators may claim to bring job opportunities to rural communities, but given the previously-cited occupational hazards of working at a CAFO (see ‘2. Worker Safety’), “local workers who are accustomed to making their own decisions and working in a humane environment typically do not work for CAFOs” (John Ikerd). Ultimately, corporate consolidation upholds an industrial agricultural system which is socially, economically, and environmentally destructive.

Regulatory Changes

-

Local Ordinances and Senate Bill 391

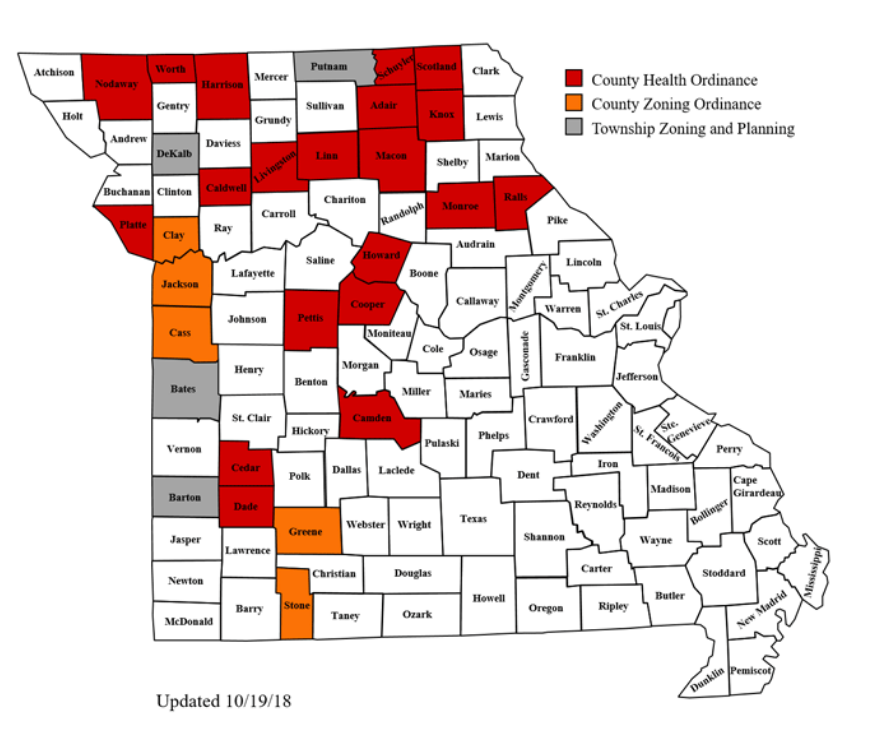

For the most part, state agencies regulate CAFO activities in Missouri. However, local governments used to have the power to establish additional rules and fees for animal feeding operations (AFOs) in their jurisdiction through county health ordinances. County health ordinances outline measures to protect public health. Examples of Missouri county health ordinances concerning AFOs include air quality restrictions, facility acreage requirements, county fees, and financial security measures like surety bonds.

In 2019, Republican Senator Mike Bernskoetter sponsored Senate Bill 391, which dictates that county health ordinances may not impose standards for agricultural operations which are inconsistent with or more stringent than state standards. The bill’s primary backers were the Missouri Farm Bureau and the Missouri Cattlemen’s Association. At the end of the legislative session, Governor Mike Parson signed it into law. SB 391 substantially undermines local power to control CAFOs, however zoning ordinances may still regulate CAFO activities.

Before SB 391 came into effect, 29 of 114 Missouri counties had additional AFO restrictions. See the MU Extension’s map and list of these restrictions here.

-

COVID-19 Rule Suspensions

In the spring of 2020, Governor Mike Parson suspended a number of regulatory rules for CAFOs. The COVID-19 emergency has disrupted transportation and prevented some CAFO operators from bringing their animals to slaughterhouses and meat processing facilities. Therefore, the DNR has allowed facilities to house more animals on-site than they may be constructed and permitted for. Typically, increased animal capacity prompts new permitting requirements; greater buffer distances from surrounding homes and buildings; neighbor notices; modifications to confinement buildings and waste storage facilities. During COVID-19, these human and environmental health precautions have been overlooked to allow “owners and operators to adapt to temporarily elevated animal numbers without adding additional paperwork and permitting application requirements.”

Facilities are still expected to follow this emergency management plan and abide by all water-quality protection requirements; however, DNR has not announced any additional oversight nor methods of tracking facilities with temporarily-elevated animal capacity. The rule suspensions were set to expire on June 15, 2020, but Governor Parson issued an Executive Order on June 11, 2020 that will extend these suspensions until December 30, 2020. Read more about the rule suspensions and MCE’s concerns here. As a Watchdog, be mindful of the following additional concerns to document and report:

- On-site animal slaughtering

- Improper disposal of dead animals

- Carcasses in wastewater lagoons, fields, waterways and roadsides

- Indicators of increased animal capacity

- Increased noise

- Increased odor

- Animals outside of buildings or in informal confinement structures

- Illness among CAFO workers

Even though Governor Parson has extended regulatory rule suspensions for CAFOs through December 30, 2020, DNR has the authority to reinstate these rules sooner if it sees fit. We encourage Watchdogs to call, email, and/or write letters to the DNR and demand that these rules be reinstated immediately.

-

On-site animal slaughtering

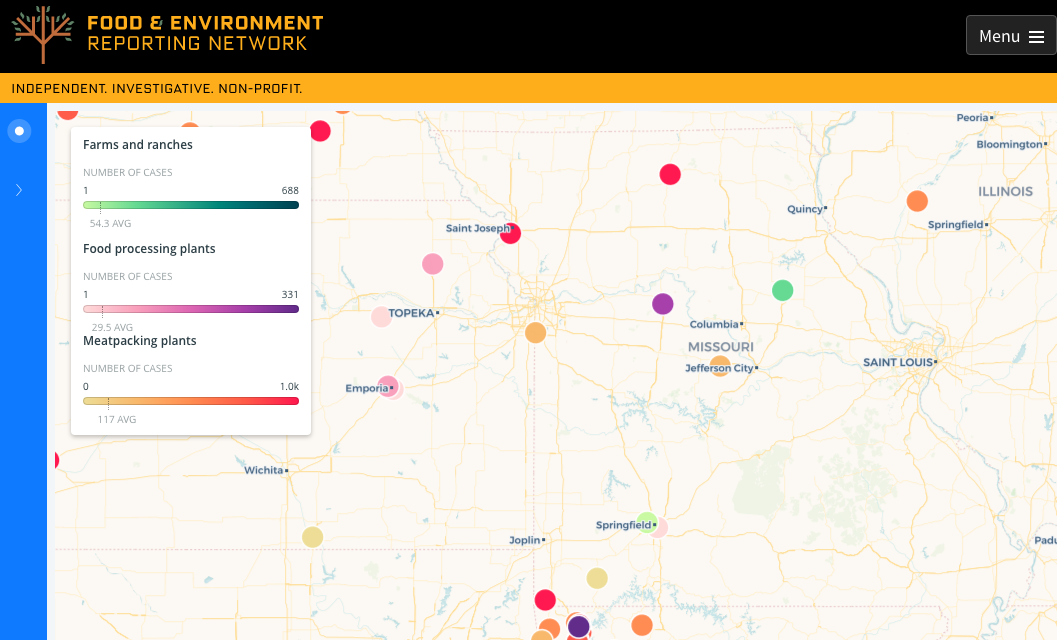

During 2020, a number of slaughterhouses and animal processing plants have been forced to close due to COVID-19 outbreaks. Like the CAFO industry, the meat processing industry is heavily consolidated such that about 50 plants are responsible for processing upwards of 95% of American meat (New York Times). This means that each plant processes millions of pounds of meat each year and each plant closure has a massive impact on the supply chain.

In some cases, CAFO operators have started rerouting their animals to different slaughterhouses and processors, which further increases the processing volume at the plants that are open. According to the ASPCA, “The animals who are not re-routed to different facilities are generally ‘depopulated’ or ‘culled’ on-farm, meaning killed en masse by methods that can be incredibly inhumane.” One gruesome example of this is the ventilation shutdown method that whistleblowers recently exposed at Iowa’s largest hog operations (warning: graphic content). According to The Guardian, “At least two million animals have already reportedly been culled on farm” as of April 29, 2020 and this will likely continue. Animal culling itself is not illegal, but CAFO operators may be using methods which raise concerns around animal suffering and proper disposal.

As of summer 2020, MU Extension has been working with the Missouri Department of Agriculture (MDA), Missouri Department of Natural Resources (DNR), United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). and Missouri Pork Association to develop guidelines for depopulating swine herds due to COVID-19. Ideally, these guidelines will minimize environmental and human health impacts. However, it remains unclear if certain methods have been approved for on-site slaughter and if they are applicable to non-swine livestock. Read more about the collaboration and access informational resources here.

-

Improper disposal of dead animals

CAFOs expect a certain amount of dead animals – “mortalities” – as part of their normal operations. Therefore, CAFOs must address mortality management in their Nutrient Management Plan (NMP) and many facilities have designated areas to compost mortalities. However, there is a difference between these “routine” mortalities which are expected as a result of normal operations and “mass” mortalities: “An unexpected loss of large numbers of animals that result from events such as disease, acts of nature, or equipment failure” (DNR Role in Mass Mortality).

COVID-19 cullings are considered “emergency mortality management”; operators should therefore follow these procedures. There are five acceptable methods of emergency mortality management– composting, burying, incinerating, rendering and landfill– which MU Extension team covers in this presentation. According to MU Extension, “Missouri law requires that carcasses be disposed of within 24 hours of death” and “DNR must approve CAFO producer plans for mass mortality disposal”.

Note the following:

- Burial is the most commonly-used mortality management method during disease outbreaks, but CAFOs are not allowed to use this method for routine mortalities and it may present groundwater pollution concerns

- Burial and composting are not allowed in sinkholes, caves, mines, or floodplains

If you see exposed carcasses and/or bones on or near CAFO sites, this may indicate improper disposal of dead animals. You should take photos and report these concerns to the Missouri Department of Agriculture (MDA) Animal Health Division at (573)-751-3377. See Additional Reporting Resources for details.

-

Indicators of increased animal capacity

The suspended rules allow facilities to keep more animals on-site than their permitted capacity to accommodate for transportation disruptions and other impacts of COVID-19. Housing more livestock in the same amount of space increases the risk of lagoon overflow, animal mortalities, and overapplication of manure. Since CAFOs should be setback from roadways, residence, and public buildings, it may be hard to observe increased animal capacity, but be mindful of the following:

- Increased noise

- Increased odor

- Increased manure production

- Animals outside of buildings or in informal confinement structures

If you start to notice these signs of increased animal capacity, note the date and duration of your concerns. Document your observations as best you can by recording noises, taking pictures of animals outside of buildings, and/or describing odors. Even under normal circumstances, neither state or federal policy regulates concerns like noise and odor. However, documenting these as impacts of the COVID-19 regulatory rule suspension supports our argument that regulations should be immediately reinstated.

COVID-19 among CAFO workers

Like workers in slaughterhouses and meat processing plants, Missouri CAFO employees have reportedly been forced to work

despite showing symptoms or receiving positive test results for COVID-19. The previously-cited living conditions for migrant CAFO workers like crowded, company-owned housing and transportation may increase exposure to the virus. Furthermore, personal protective equipment (PPE), social distancing measures, and testing may not be provided at work environments. See a map of COVID-19 outbreaks in our food system here.

Unfortunately, migrant workers in particular are hesitant to voice their concerns to employers and regulators or identify themselves to the media because they work on temporary visas which their employers may terminate. Find resources on how to advocate for food system workers’ rights through the Food Chain Workers Alliance.