As of January 1, 2019, there were 506 concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs) in the state of Missouri. While other states – like our neighbors in Iowa – have significantly more CAFOs than we do, Missouri may have the weakest rules governing CAFOs in the entire country. CAFOs present a slew of environmental, human health, and socioeconomic challenges; if you are unfamiliar with CAFOs and their impacts, see MCE’s CAFO story map to learn more.

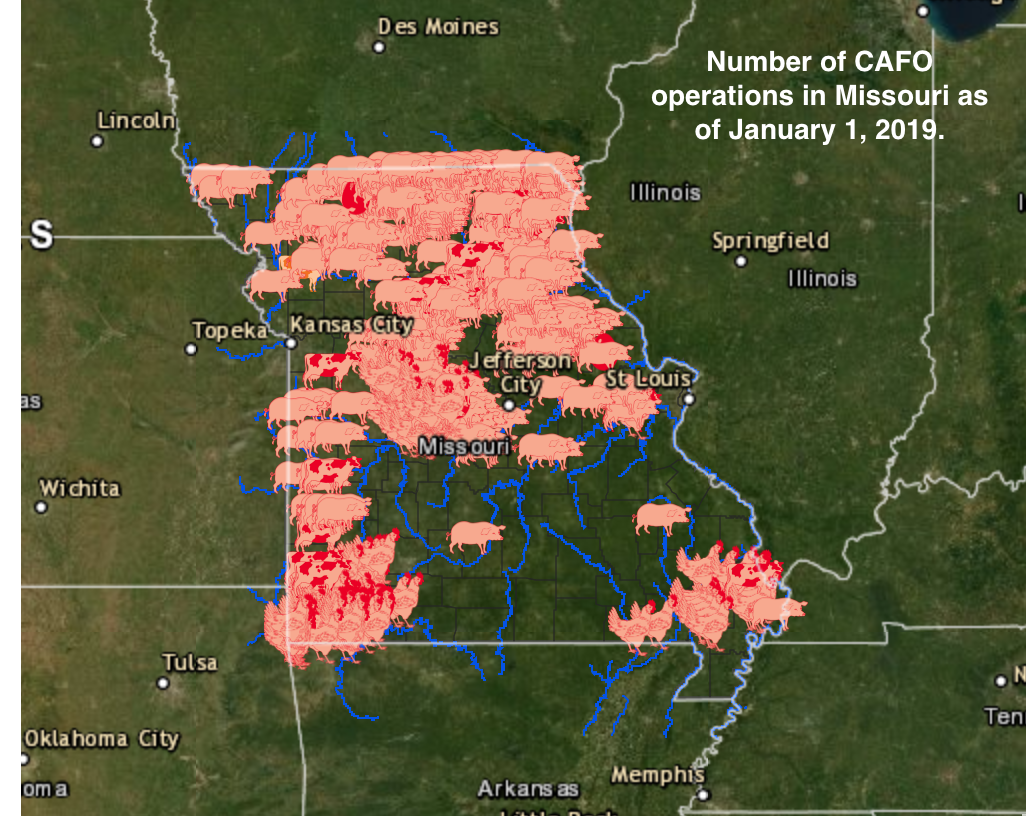

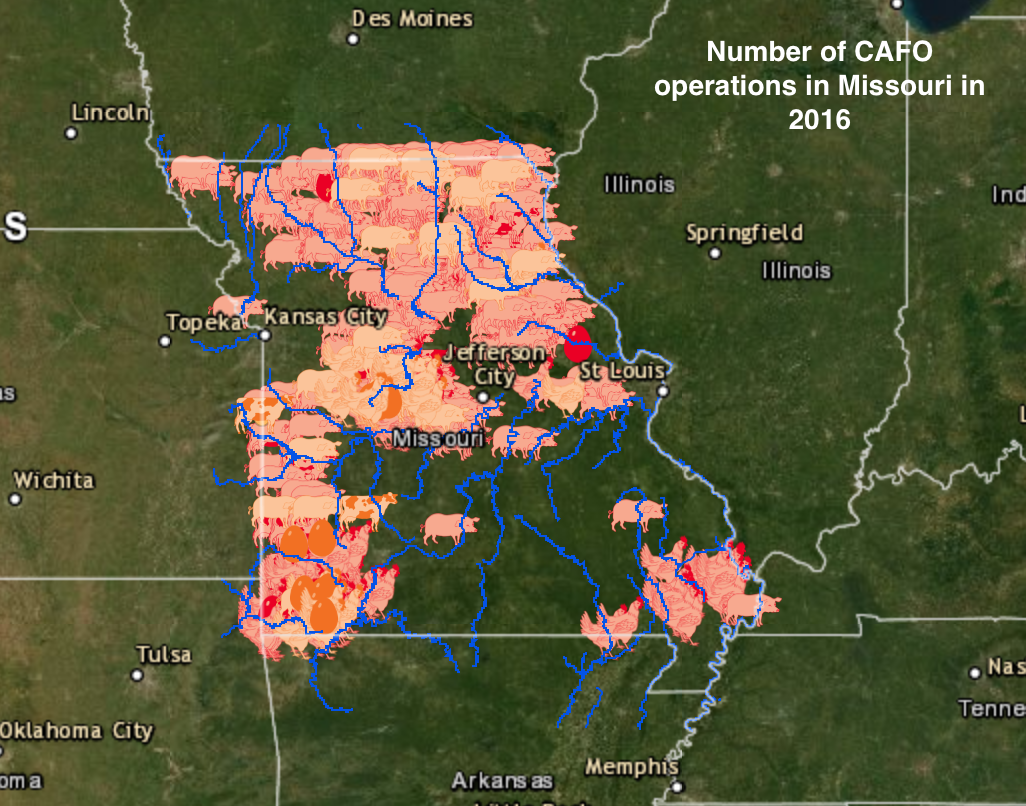

Over the past decade, the Missouri legislature has promoted CAFO expansion in our state. It should serve as evidence that just three years ago, 56 out of 525 CAFOs in the state were categorized as Class II CAFOs – the “smaller” size of CAFO operations – as shown in pale pink on the lefthand map. Now, only three of 506 CAFOs in our state are Class II, while the majority are over 500 Class I (large) CAFOs, indicated by the concentration of darker red on the righthand map. At this time, we may not have a significant number of CAFOs moving into the state, but those that exist are scaling up. Various pieces of state legislation have created favorable conditions for establishing new CAFOs and expanding existing ones:

Private nuisance claims

CAFOs are defined as a private nuisance: when an individual or private entity unreasonably interferes with an individual’s use or enjoyment of their property, a lawsuit may be brought to remove that nuisance. In 2011, the Missouri legislature amended the law of private nuisance as it applies to CAFOs so that only economic damages such as property value would be recoverable: essentially, as a result of this law change, nuisance claims based on odor, noise, human health and environmental quality can no longer be brought to court.

Clean Water Commission board

The Clean Water Commission is responsible for reviewing CAFO permit applications and establishing water quality standards. There are seven members on the board of the Clean Water Commission. When the Missouri Legislature first established the board, no more than two board members could represent agricultural or mining interests, and at least four members would represent the public interest. In 2016, House Bill 1713 changed the composition of the Clean Water Commission, such that up to six of seven members on the board could represent agricultural interests. This is a case of the “fox watching the henhouse.” See MCE’s blog post about the impacts of House Bill 1713.

County health ordinances

Most recently, Governor Parson signed Senate Bill 391 into law at the end of the 2019 legislative session on May 17, despite numerous and ongoing efforts to block it. Governor Parson has expressed strong personal support for the bill: “I think it’s a good thing for our farmers and ranchers across the state and I think it’s a good thing for the future of Missouri” (Brownfield Agricultural News). Senator Mike Bernskoetter (R – Jefferson City) sponsored the bill, which was introduced at the start of the 2019 legislative session. It reads:

Under this act, any orders, ordinances, rules, or regulations promulgated by county commissions and county health center boards shall not impose standards or requirements on an agricultural operation and its appurtenances that are inconsistent with or more stringent than any provisions of law, rules, or regulations relating to the Department of Health and Senior Services, environmental control, the Department of Natural Resources, air conservation, and water pollution.

For 50 years, Missouri Coalition for the Environment has engaged the state legislature on the issues we value; this year we entered the legislative session with one of our five priorities to “preserve the option of Missouri counties to determine how close a concentrated animal feeding operation (CAFO) or factory farm can be located to neighboring properties,” which SB 391 takes away. Read MCE’s full 2019 Legislative Session debrief here.

It was difficult to oppose Senate Bill 391 because its primary backers – notably, the Missouri Farm Bureau and the Missouri Cattlemen’s Association – were reluctant to consider any serious amendments to the bill, which would effectively eliminate local governments’ control over CAFO regulation and nullify any county health ordinances that currently regulate CAFOs. The bill was debated for 15 hours on the Senate floor, including an overnight filibuster a few weeks prior to the end of the legislative session. Eventually, the bill was amended to include:

-

-

- a Joint Committee on Agriculture

- increased notification for neighboring properties if a landowner wants to build a CAFO

- bans on CAFO construction until an operating permit is acquired

- buffers for the application of liquid animal waste on farm fields with varying setbacks for neighboring properties and water sources like rivers, lakes, and drinking water wells

-

The Missouri Farm Bureau and the Missouri Cattlemen’s Association lobbyists opposed amendments that would have 1) allowed a local vote to retain local control, 2) restored the public majority on the Clean Water Commission, and 3) banned foreign ownership of Missouri’s agriculture land, requiring currently foreign owned land to be sold back to Americans.

At the start of 2019, 20 out of 104 counties in Missouri had local health ordinances with more stringent requirements for CAFOs than the state’s minimum standards. Taney, Stone, and Cooper counties all passed local health ordinances before SB 391 was signed into law on August 28; it is expected that legal challenges to SB 391 will address whether the law may be implemented retroactively, making these and any other existing local health ordinances ineffective. The bill generated significant concern throughout the state of Missouri, evidenced by its coverage in Missouri Farmer Today, The Joplin Globe, The Kansas City Star, The Columbia Missourian, and by the Missouri Rural Crisis Center. SB 391 also received national attention in Pacific Standard magazine and The New Food Economy.

At the start of 2019, 20 out of 104 counties in Missouri had local health ordinances with more stringent requirements for CAFOs than the state’s minimum standards. Taney, Stone, and Cooper counties all passed local health ordinances before SB 391 was signed into law on August 28; it is expected that legal challenges to SB 391 will address whether the law may be implemented retroactively, making these and any other existing local health ordinances ineffective. The bill generated significant concern throughout the state of Missouri, evidenced by its coverage in Missouri Farmer Today, The Joplin Globe, The Kansas City Star, The Columbia Missourian, and by the Missouri Rural Crisis Center. SB 391 also received national attention in Pacific Standard magazine and The New Food Economy.

At the end of August, the Cedar County Commission, the Cooper County Public Health Center, the nonprofit Friends of Responsible Agriculture and three property owners filed a suit against the new law on the grounds that it violates the Right-to-Farm amendment. In response, Cole County Circuit Judge Patricia Joyce placed a temporary injunction on the law on August 19 and set a hearing for September 16 at 9:00 AM in Cole County. The following day, Governor Mike Parson’s spokeswoman Kelli Jones made a statement that the administration would make “an aggressive legal response to this unfounded temporary restraining order”.

On August 31, another Cole County Judge, Dan Green, set aside the temporary injunction on the law after the suit which had been filed by Cedar County, Cole County, and Friends of Responsible Agriculture. The first hearing has been rescheduled for December 9, 2019. MCE awaits further legal action.