Not all farming practices were created equal. While one hundred years ago, much of the nation’s animal agriculture production occurred in open fields, today most animals raised for human consumption live in Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations (CAFOs) or factory farms. CAFOs threaten public health, animal health, the health of the operations’ workers, water quality, air quality, and soil health.

Animals in these operations live indoors, often without access to adequate space to stretch their limbs or turn around. These animals live in barns, often by the thousands, making it easy for sicknesses to transfer quickly throughout the herd if one becomes ill. Given that these animals do not roam open fields, they excrete their waste right inside the barns. With so many animals in one confined space, the amount of waste generated is substantial. These operations transfer the animal waste into large pools called lagoons, where the waste is then regularly applied on adjacent farm land or exported to other landowners who will apply the waste on their land.

Maps of CAFOs

MCE has made a map of all of the CAFOs in the state, a story map of the health impacts of CAFOs, and a more detailed look at where CAFOs are in relation to sensitive water and soil resources. Check out each of these maps below!

As stated above, CAFOs are only getting bigger in Missouri, creating more environmental and health impacts, which we’ve outlined below. To help MCE continue our work to create a just and sustainable food system, including fighting to proliferation of CAFOs in Missouri, consider donating today.

Below is a Story Map illustrating how different soil types, geological features, and water resources across the state are more susceptible to CAFO waste contamination and thereby where Missourians may be more susceptible to the harms described above. To view the Story Map in a web browser all by itself, click here.

We encourage you to explore the Department of Natural Resource’s AFO map to learn the landscape of factory livestock farms in Missouri.

Missouri CAFO Hog Waste Spill Data Map for Smithfield Foods

The Socially Responsible Agriculture Project (SRAP) reviewed public records and found that Smithfield Foods spilled more than 7.3 million gallons of hog waste throughout Missouri, polluting our late and waterways.

Looking at 15 years of public data SRAP found that Smithfield Food’s concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs) in Missouri experienced an average of 28 waste spills per year in our state. This equals more than 300,000 gallons of waste every year. You can view their map here.

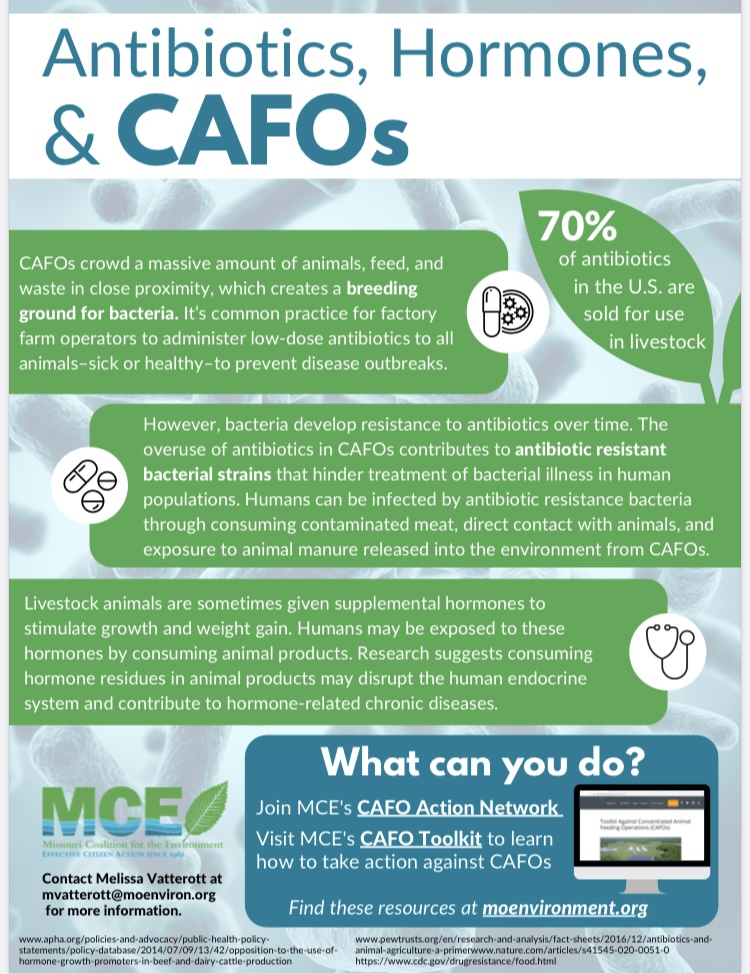

CAFO Harms Fact Sheets

Check out MCE’s quick-read fact sheets on the various harms of Concentrated Animal Feed Operations (CAFOs) below!

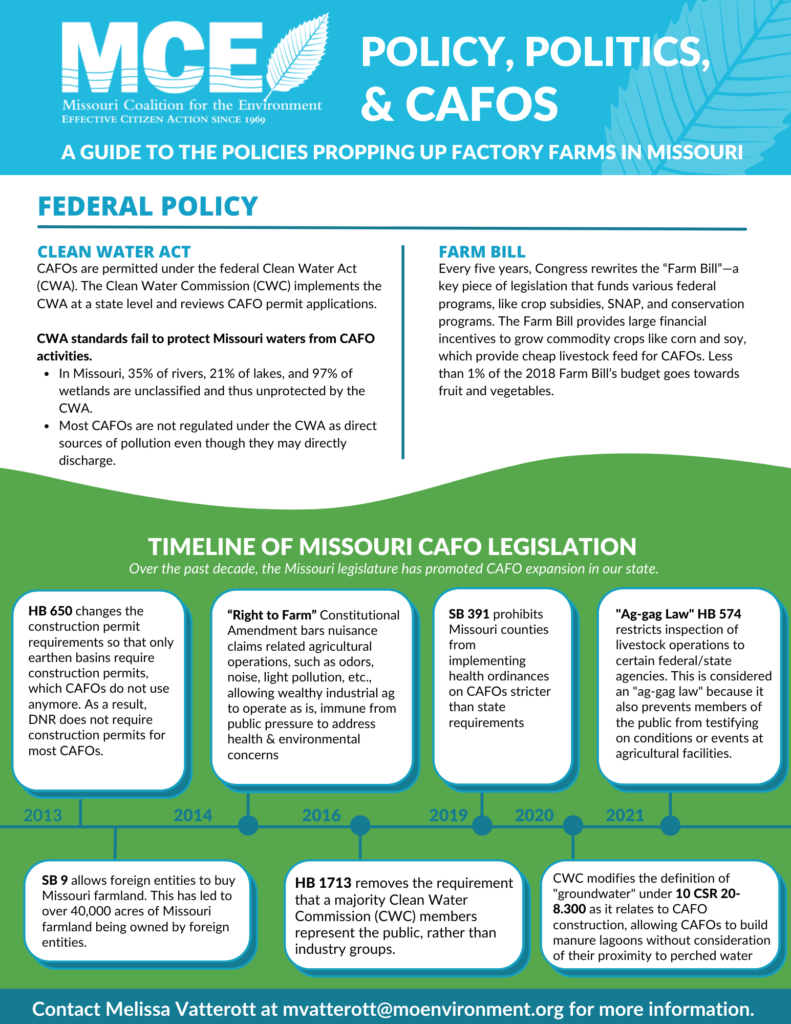

Timeline of CAFO Policy

MCE Policy Team created this timeline in partnership with Missourian Cheryl Marcum

Missouri passed a corporate farming law that banned large corporations from owning land and operating industrialized farms within the state. (“Animal Factory,” David Kirby, 2010, p. 193; Missouri Revisor of Statutes – Revised Statutes of Missouri, RSMo Section 350.015)

“[D]uring the final exhausting hours of the Missouri legislative session, a little-noticed amendment was piggybacked onto an economic development bill that would exempt Sullivan, Mercer, and Putnam counties from the corporate farming law for the raising of swine. . . The amendment also gave Premium Standard Farms access to millions of dollars in new financing for their planned ‘Missouri operations” . . . They proposed a megacomplex consisting of 96 hog buildings and 12 lagoons with a total capacity of over 240 million gallons of feces and urine. It would house about 106,000 head and be built within a mile of nearly thirty family homes.” (“Animal Factory,” David Kirby, 2010, p.193)

Hog market collapsed due to insufficient slaughter capacity.

Murphy Farms was raising about 900,000 pigs under contract in Iowa.

In September 1999, Smithfield Foods, the nation’s largest hog producer, began its pending purchase of Murphy Farms. (Murphy Farms sells for $460M – Triangle Business Journal (bizjournals.com))

January 2000, Smithfield Foods Inc. announced that it completed its acquisition of Murphy Family Farms Inc. (Smithfield Seals Merger with Murphy; The CAFO Industry’s Impact on the Environment and Public Health | Sierra Club)

“[T]he [EPA] 2008 final rule, unlike the 2003 rule, which categorically required a permit for any CAFO with a ‘potential to discharge,’ the revised regulations call for a case-by-case evaluation by the CAFO owner or operator as to whether the CAFO discharges or proposes to discharge based on actual design, construction, operation, and maintenance.” (Implementation Guidance on CAFO Regulations – CAFOs That Discharge or Are Proposing to Discharge)

In 2013, the Missouri legislature changed the statute that formerly outlawed foreign entities from owning Missouri farmland by slipping language into SB 9 at the end of the session so it received no public debate. SB 9, sponsored by Sen. Pearce (R) and Rep. Casey Guernsey (R), opened up 1% (289,000) acres of Missouri farmland to foreign corporate ownership. On Aug. 2, 2013, Gov. Nixon vetoed it. The Missouri legislature overturned the veto and two weeks after that, Chinese corporation Shuanghui International Holdings Ltd., now Shuanghui Group (later changed its name to WH Group), bought Smithfield Foods and began shipping as much as 25% of its pork to China. WH Group controls over 25% of U.S. pork and owns over 40,000 acres of Missouri farmland. They own Premium Standard Farms in northern Missouri, bought in 2006.

In 2013, HB 28 became law, removing the requirement that CAFOs must obtain construction permits prior to constructing facilities. This had the effect of also changing the neighbor notice requirement for Class I CAFOs – only requiring notice for operating permits. This bill also changes what and how often operators of flush system animal waste wet handling facilities must inspect.

Right to Farm constitutional amendment passed in the August primary election. It negates nuisance lawsuits against CAFOs.

April 14, 2015, Mo. Supreme Court issued opinion declaring CAFOs are permanent nuisances and eliminated citizens’ ability to make nuisance complaints for non-economic damages against CAFOs.

In 2015, the legislature changed the law and opened a large loophole that allowed foreign corporate interests to bypass reporting their land purchases to the Missouri Department of Agriculture. Omnibus SB 12, sponsored by Brian Munzlinger (R), created a loophole making it impossible or nearly impossible to track foreign land purchases.

After the Clean Water Commission (CWC) denied two CAFO permits, Senator Munzlinger introduced House Bill 1713 which altered the composition of the Clean Water Commission, removing a requirement that reserved four of the seven seats for members of the general public. This bill became law, changing the composition to allow up to six of seven members on the board to represent agricultural interests. Shortly thereafter, a new commission was appointed.

“Congress removed the minimal regulations placed on agricultural air pollution in March 2018.” (https://investigatemidwest.org/2018/06/02/local-communities-fight-air-pollution-from-large-animal-farms/)

The Missouri Senate confirmed appointees to the CWC with close ties to the corporate, factory-farm agriculture industry. The new commission immediately issued permits to two CAFOs that were denied by members of the previous CWC. (MCE Fall 2018 Alert)

SB 782 became law in 2018, weakening Missouri’s Clean Water Law by limiting the DNR’s ability to intervene only after agricultural runoff pollution has been proven to “render such waters harmful, detrimental, or injurious to public health, safety, or welfare.” It essentially calls for cleaning up pollution after it happens instead of preventing it.

A CAFO is a “point source,” but all of the millions of gallons of waste they produce that is spread in our state are defined as “non-point source,” and therefore, not regulated. “States report that nonpoint source pollution is the leading cause of water quality problems.” (US EPA)

May 31, Governor Parson signed SB 391 into law, prohibiting county commissions and county health center boards from promulgating any orders, ordinances, rules, or regulations that “impose standards or requirements on an agricultural operation and its appurtenances that are inconsistent with or more stringent than any of law, rules, or regulations relating to the Department of Health and Senior Services, environmental control, the Department of Natural Resources, air conservation, and water pollution.”

Cedar County Commission and Cooper County Health Board et al. filed a lawsuit against the state to challenge SB 391.

Legislature passed HB 574 which limits who can inspect agricultural facilities to state and federal agriculture and environmental officials and law enforcement in an apparent effort to bar local health departments from viewing the facilities. Considered an “Ag-gag Law” because it also prevents members of the public from testifying on conditions or events at agricultural facilities. (MCE’s “Policy, Politics, & CAFOs,” 2022.)

Legislature passed HB 271, prohibits local standards or requirements on “an agricultural operation and its appurtenances that are inconsistent with, in addition to, different from, or more stringent than state laws and regs.” This law particularly obstructs Cooper County’s new health ordinance which was “different from” applicable state law.

MCE’s CAFO Action Network

Sign up below to join our network of members who we can call on when there are time-sensitive actions to take regarding factory farms, otherwise known as concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs).

CAFO’s and Racial Inequity

Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations (CAFOs) threaten our rural economies, public health, and environmental quality. All of these negative impacts disproportionately affect low-income communities and communities of color because of where CAFOs operate and who they employ. Therefore, CAFOs are an example of environmental racism: “the disproportionate impact of environmental hazards on people of color” (Energy Justice Network).

Based on 2019 data, all of Missouri’s most CAFO-dense counties have higher poverty rates than the state average. In our state, the population in these CAFO-dense counties happens to be over 85% white (2019 Census). However, in states like North Carolina, not only are CAFOs about seven times more common in high-poverty areas, they are also approximately five times more likely to be found in majority-nonwhite communities (Wing, et. al.). Why are CAFOs located in these areas? Low-income communities and communities of color typically have the least financial and political resources to prevent hazardous operations like CAFOs from moving into their communities. CAFOs may force small farmers out of business and become one of the only job providers in the area, which makes some employees and residents reluctant to voice their concerns. As a result, they face the most direct economic, environmental, and human health consequences from living near these operations. In North Carolina, hog CAFOs are often built in the same communities as former slave plantations. Over a century after being “liberated” from the abuses of slavery, black residents continue to experience high rates of poverty, negative health outcomes, poor housing and diminished environmental quality (Wendee).

Many Missouri CAFOs are located in majority-white communities, but we know that the U.S. agriculture industry has relied heavily on Latinx immigrant labor since the 1942 Mexican Farm Labor Agreement. According to the USDA, 64% of farm laborers, graders, and sorters were ‘Hispanic’ and 55% were not born in the United States as of 2018. The demographics of CAFO labor are not well-documented or reported at the state or national level. However, studies of job-related risk for Missouri CAFO workers such as thisindicate that immigrant labor is increasingly common in the CAFO industry and Missouri CAFOs are no exception. Often, immigrant workers are not given job safety training or adequate information about numerous occupational health risks associated with CAFO work. When they are, materials usually are not presented in their primary language (Ramos, et. al.). Overall, “Many immigrant farmworkers are socially, economically, and legally vulnerable which may increase their occupational risks and promote under-reporting of workplace hazards and injuries due to fear of losing their job or being undocumented” (Ramos, et. al.). CAFOs and other forms of industrial agriculture exploit low-wage immigrant workers to minimize their costs and increase their profit margins.

As you can see, CAFOs are part of an industrialized food system which produces and perpetuates socioeconomic and racial inequities. MCE is working to promote a thriving, just food system across Missouri. Such a system involves producers who care for their land and the life on it, the air and water around their land, their workers, and their customers. It involves eaters who have access to affordable, healthy, culturally-relevant food that is grown responsibly. Such a system is resilient and diverse, involving multiple small-scale growers, food distributors, and food outlets and employing individuals of all backgrounds in the food system at a livable wage. Such a system is resilient against threats of climate change and pandemics and is anti-racist and inclusive to ensure people of all walks of life can be employed and be nourished by our food system. MCE is working toward this vision of a thriving, just food system through our efforts to:

- Combat the spread of CAFOs

- Learn more about our CAFO work here

- Support our CAFO advocacy fundraising campaign to continue this work

- Combat threats to food security

- Learn more about food access in our region here

- Read about how St. Louis Food Equity Advisory Board is working to improve food access here

- Support small-scale producers who care about people, animals, and the environment

- Learn more about our Known & Grown STL program, a brand for environmentally-responsible farmers within 150 miles of St. Louis, here

- Lift up beginning farmers and farmers of color who are currently discriminated against in our industrial food system

MCE’s CAFO Action Toolkit

This Toolkit gives you the resources that you need to “Watchdog” Missouri CAFOs for regulatory violations, environmental concerns, and various other CAFO activities which impact human, animal, and economic well-being. MCE hopes to expand and improve this Toolkit over time. We welcome your feedback on how to make these resources more accessible and effective for our CAFO Watchdogs! Please contact Policy Director Melissa Vatterott at mvatterott@moenviron.org with any questions and comments about the Toolkit.